Sorry to offload on you after so long, but isn’t that why we’re here?

I’ve been thinking about what silence means and how it’s changed over time and how it performs in various contexts. Since this musing begins in the 90’s and PJ Harvey was my 90’s rock God, let’s start with her lyrics:

I don’t know what silence means. Silence could mean anything.

-PJ Harvey

I arrived loud and proud in San Francisco in 1992, when activism meant filling the streets with noise and flair. I remember marching in my fun fur leopard print shorts and shooting my green toy water gun above my head. I sprayed hot horny queers, artists, strippers and activists— friends of mine in ACT UP.

We didn’t have Twitter threads, Instagram posts or cellphones back then. Zuckerberg was a pedestrian second grader, getting ignored by girls. I lived in a dusty Victorian with 3 or 4 rotating Craigslist roommates. We shared one landline and an answering machine fastened to its base with scotch tape. Most messages on that machine weren’t for me, but I always got the scoop about where and when to show up. Whether it was ACT UP, Women against Domestic Violence, Pink Saturday, Gay Pride, The Dyke March, Food Not Bombs or Exodus, a lesbian sex club where I volunteered as a bouncer.

ACT UP S.F. was no joke. Silence equaled death. We pounded the pavement and yelled until we lost our voices. Our anger was beautiful and hoarse. Evangelical politicians blamed the sick while silently doing jack shit to stop our friends from dying by the thousands. Our bitchy bombastic rage threw us into action. And I needed to revolt alongside other gay bodies loudly to stab the fog of silence. We paraded in the Castro past Condomania and A Different Light; past the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence who stepped in for the last leg to Market Street.

Activism worked in ways I could see and feel every day.

Now, 25 years after a group of us unionized the Lusty Lady Peepshow in North beach, the California Supreme Court passed AB5, addressing employee misclassification. I’d seen first hand that conditions were worse in the clubs. Club owners found innovative ways to steal as much money as possible from strippers, changing the name of their illegal kick back to obscure wage theft.

When AB5 passed, strip club owners began to charge strippers to pay our own wages and forced bizarre contracts without time to review them. In order to work, dancers had to sign away all our rights, agree to be charged a fictional rent, agree to not sue for discrimination, or agree that they were in fact not a worker, but a customer.

It scared me to watch strippers I admire and adore hand over that much of their hard-earned cash when I knew they had young kids at home and rent to pay. But they bent to the will of the new extortion model like a blade of grass on a windy hill—a hill workers voices go to die because they think they are powerless.

Federally, I knew strippers were employees. But post AB5, state wide, no one could tell us differently. We could organize. We could unionize after decades of pay-to-play bullshit extortion, blatant discrimination, tip stealing, wage theft and coercion.

Our base of strippers grew for a few months and other organizations showed up to show their support like Me Too, DSA, IASTE and some incredibly generous labor lawyers who are still hoping we will make some bold moves. When the pandemic hit, strip clubs closed indefinitely, and our livelihoods vanished overnight. Many radicalized strippers moved, quit, changed jobs, hopped on Only Fans or procured paid dates with their regulars. Most strippers I know mostly struggled to keep the lights on and the dogs fed. Often, a mental health crisis haunted a member or two and for good reason. Life was terrifying and unrecognizably stressful.

As for me, it was maddening to not have any real structure in my life. I was used to stripping twice a week and teaching writing classes for UCLA extension, but my life got small and wilted.

Strippers United, previously known as Soldiers of Pole, held organizing meetings online in an effort to remain connected to the cause. Zoom meetings were a novelty at first, but soon became a strange maze of mixed signals. Words were garbled, hard to interpret. Tone was tough to decipher. Faces froze mid-sentence at the exact wrong moment. I’d catch a smirk, or occasional smile but lots of people turned off their cameras.

Speaking into a void is not a back-and-forth conversation. It is lonely. It is prickly and it is confusing. It was challenging to articulate tough issues in a way that landed softly enough, sincerely enough or clear enough to convey honesty or enthusiasm or simple friendship. But no matter what happened, I felt like I was doing it all wrong. I started to mark on a paper when anyone acknowledged that I existed. Sometimes I’d say what I was hearing or respond directly in case the person speaking seemed like they were straining to be heard. It was relayed to me that folks didn’t want to feel like they had to respond to me because I was perceived as having power and clout. I understood that this was because of white supremacy. And I had my own anti-racism work to do, which I did. It felt like there was talk about important conversations that needed to happen, but all I felt was stonewalled. For a while, I got comfortable with being uncomfortable. Silence was a weapon to put me in my place, a place alone and exiled from the organization I built for strippers to have for that exact reason.

I can’t pinpoint exactly when trust eroded for me or when I felt so invisible that I wanted to die. Faces tightened and eyes narrowed. I dreaded online meetings, which often felt like a slow unravelling of misunderstandings and unresolved conflicts. Quarantine dragged on mercilessly. Any sense of normalcy slipped away like squinting directly into the sun until the road is a blaze of liquid light.

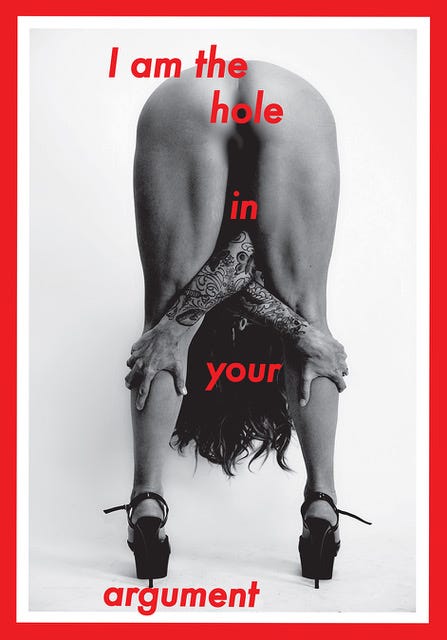

Pretending a person does not exist is a way to socially behead a person in the group. As a sex worker, I realize that I am more sensitive to this because of deep societal stigma and workplace violences so embedded in my emotional wiring, they throw off sparks and set off fires. A lifetime of being cast out, belittled and depicted in film and tv as someone to kill as joke over and over gets to one.

Instagram became another stripper warzone. Vaguely stern monologues were heated digital breadcrumbs that were harder and harder to follow. Controversy swirled in stories, videos and missed conversations. Public conflicts churned in DMs. Cyber bulling in the interest of upending power structures were tossed off like teargas hurled from behind screens. Silent scorn was a nuclear weapon wielded at anyone who didn’t do what one wanted, say what needed to be said, or apologize on command.

I tried to talk less; I tried to listen more. But I did that wrong too. Did I really sound like a know-it-all like they said? Should I stop talking about my life? How long do they want me to not speak to them? A month, six months, a year? I listened. I heard some things. One of the things I heard about members of my organization was “they don’t like AB5.” I am not sure I know who “they” are, but I can guess. They were the strippers who were discarded and wrongly terminated by their shady employer.

They were told that they’d loose their flexible schedule if they become employees as if there is any relation to those two things. They were told the clubs will shut down if they are employees. These are all completely untrue.

Strip club owners have spun a fable where being an employee sucks and they’ve used draconian measures to enforce the story by firing strippers along racial lines.

Businesses thrive on this disinformation. The disinformation was concocted in order to protect their financial interests. They are used to treating strippers poorly without meaningful penalties. They are used to intimidating strippers into being silent. When strippers win lawsuits, they are forced to sign NDA’s so even a financial victory is silenced. The last thing these employers want is strippers commiserating about unfair, illegal labor practices and sharing notes.

Strip club owners want workers to dislike AB5 instead of insisting on our own personal, bodily safety, job security, an anti-discrimination policy with teeth. Strippers who don’t like AB5 are protected by title 7 and are not if they are independent contractors. Arguing, dragging and bickering instead of focusing on building power and worker solidarity is what strip club owners want.

Their biggest fear is that strippers unite.

This is where we are. The violence of silence has done its work well. Weaponizing silence is the norm.

It’s time to rupture the silence. But how?

Maybe it begins right now as neon green parrots of Highland Park dominate the hazy blue sky. Ravens click. Over 26,000 Los Angelenos have died from Covid. I haven’t danced with my beloved coworkers hip to hip in nearly two years. I haven’t been inside of a club or given a lap dance since Covid. Have you? Shout it out.

California strippers are healing.