When Financial Torture Feels like Freedom

The sickly sweet taste of wage theft in your local strip club.

Dressing room selfies happen in tight breaks between clients to scrub slobber off my neck or nibble a melted protein bar. If I’m fast, I’ll have time to pee while my regular, whom the DJ calls “the strangler”—guess why? is occupied with other dancers. In one strip club selfie from 2018, I’m half-smiling and holding stacks, but my hips crack. My neck’s out. My feet ache. The selfie serves a purpose other than being a thirst trap too: It’s time-stamped proof that I exist somewhere between my pink locker and the law.

My razor sharp boredom may suggest otherwise, but I don’t hate stripping. I don’t not hate stripping. It pays better than any job I’ve had, which includes so far: teacher, editor, social worker (residential assistant for homeless youth), housekeeper, bartender, caterer, waitress, personal assistant, nanny, law firm AND hair salon receptionist, free lance writer and phlebotomist.

Economic landscapes have waxed and waned but the laws have never favored sex workers. Stripping, which is technically legal sex work, has only become more dangerous, exploitive and abusive over time. Not because of the job, but the lawlessness of craven employers who have evaded labor laws and human rights without lasting repercussions. Would more regulation help? I used to think so.

On April 30, 2018, the California Supreme Court thought so too. The Dynamex ruling passed, making it harder for employers to misclassify workers. I knew we were misclassified, but what would employee status look like in this feral space? Would we have to clock in and out like we did at The Lusty Lady? What about sick pay and work-related injuries? Would they finally fix the toilet?

Strippers have a complicated relationship with the law.

Law enforcement has never had stripper’s backs. When the cops show up at our work, it’s a sting. Dancers with vulnerable immigrant status scatter. Those who remain get slapped with a citation, or arrested for prostitution. If the club shuts down for zoning violations or multiple citations, arbitrary rules are enforced that have everything to do with moral panic— how much butt cheek strippers are aloud to show or what body part they cannot reveal— and absolutely nothing to do with legally protecting the rights of strippers.

When class action lawsuits rule in our favor, strip club owners blame the plaintiff for holding them accountable. Casual whorephobia, deflecting blame and pitting strippers against each other contributes to a workforce riddled with fear and powerlessness.

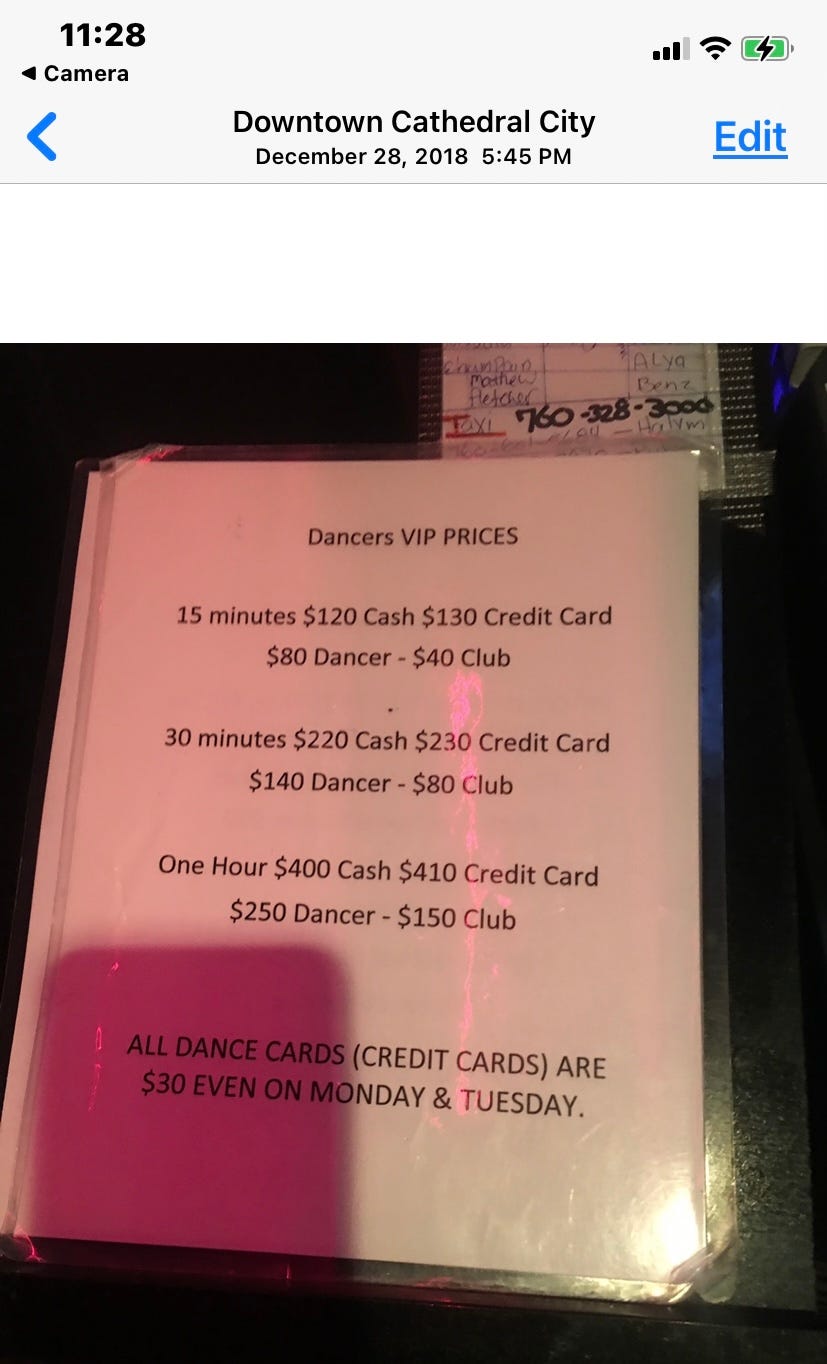

In the late 90’s, that horse shit worked on me. I shunned litigious strippers who I thought made our jobs harder when my home club paid out a significant class action settlement. As a way to get back that cash, my club charged dancers more punitive stage fees, and extreme tip gouging by way of (funny money) scrip: the-more-you-work-the-more-you-owe-method of financial torture. I thought that suing clubs was selfish and pointless because it awarded a handful of workers a payout, while we working strippers sweated it out. I was wrong.

Over ten years later, I met other stripper activists like Brandi Campbell who used lawsuits as a way to draw public attention to employers skirting labor laws. Left in the lurch with immoral employers, strippers have to sue them. It’s a legit legal tool to leverage power and give back to workers the money they are owed.

On December 17th, 2018, at an annual SWOP (sex worker outreach project) two other strippers and I decided to begin an education campaign around dancer labor rights. We used the Dynamex ruling as a jumping off point to organize dancers and begin the conversations about bargaining rights. I thought that if strippers were armed with the facts, they would want to protest harmful working conditions and fight back. I thought I could convince them that without us, a club is just a building full of bed bugs and boners.

But strip club owners and their lawyers cluttered the field with their anti-union nonsense. They cried. They moaned. They threatened bankruptcy. They cut dancer’s schedules in half, fired BIPOC dancers, LGTBQIA+ dancers, seasoned dancers, thick or disabled dancers and they blamed AB5 for their actions.

And dancers believed them. Why wouldn’t they? The law has done strippers dirty. On April 30, 2019, AB5 passed in California which codified the Dynamex ruling.

Around this time, I auditioned for a job at a well known strip club. The manager on duty looked me in the eyes and said, “You have to make your own wages.”

Imagine showing up for a job interview and being told you have to make your own wages. I thought of the labor movement and how it’s meant to go to bat for exploited, misclassified, unprotected workers. I thought about how labor unions formed to create protections and negotiating power to give workers leverage and the possibility of a financial future. The club found out about my interest in stripper’s rights and unionizing. When I showed up to work, they fired me.

What good is a pro-labor law like AB5 if it’s not enforced? How good is a labor law that is used to hurt workers?

I think one huge reason strip clubs are invested in strippers thinking they are independent contractors is the fact that contractors cannot file a wage theft claim: Wage Theft Claim Here. Also, I.C.’s cannot unionize or legally talk shop on the job. At the same time, if you’re a stripper, being misclassified can seem freeing because even though you pay to work every night, quick cash flows, managers keep iffy records of your existence, and you can slip in and out of your club with cash in hand off to the next gig.

For seasoned strippers, wage theft is the status quo. The normalization of wage theft in strip club culture and the collective willingness to be silent about is as mystifying as it is underestimated. It benefits strip clubs to lure strippers into a long con fantasy that they operate “under the radar.” Meaning, they exist above or beyond the law. They don’t. An employer who believes they are operating under the radar is a dangerous employer.

Sadly, the architects of AB5 were not thinking of the financial violence, racism and abuse happening on the shop floor in strip clubs across California. They were thinking about Teamsters.

And in November of 2020, California voters passed prop 22, a misleading and scandalous bill that allows ride share companies to continue to misclassify drivers, nullifying the entire point of AB5. But the fight is far from over. A group of drivers are suing to overturn prop 22 because it is unconstitutional.

Right now, returning to work in person is risky. Some days I miss the stripping, but most days I just miss the strippers. It is difficult to know how we will proceed? Separately, divisively, collectively, as a union—or alone.

What I do know is, when labor laws fail us, we exist. When our employers fail us, we exist. And if and when we fail each other, our rage-grins will shine in the garters of our hearts.